What is Hemophilia? Hemophilia, also spelled Haemophilia, is a group of inherited blood disorders in which blood does not clot properly (Citation 21). People with this condition experience prolonged bleeding or oozing following an injury, surgery, or even having a tooth pulled. In severe cases of Hemophilia, heavy bleeding occurs after minor trauma or even in the absence of injury (spontaneous bleeding). Serious complications can result from bleeding into the joints, muscles, brain, or other internal organs. (Citation 22). There are 2 major types of Hemophilia, labeled type A and type B. Hemophilia A is characterized by a lack of clotting factor VIII and accounts for about 90% of hemophilia cases. 70% of hemophilia A cases are severe. Hemophilia B is characterized by a lack of clotting factor IX. A very rare disorder, hemophilia A occurs about once in every 10,000 births and hemophilia B occurs once in every 50,000 births (Citation 25). |  |

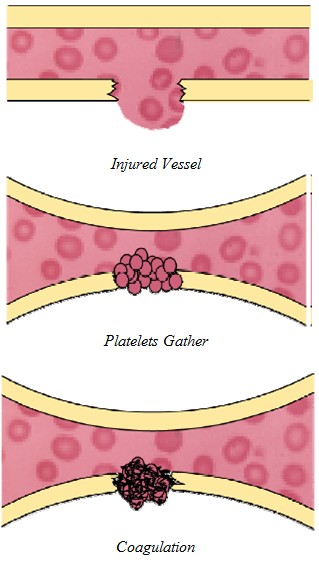

| What Causes Bleeding Disorders? To understand what causes bleeding disorders, it is important to first understand what coagulation is. Coagulation is a complex process by which the blood forms clots to block and then heal a lesion/wound/cut and stop the bleeding. It is a crucial part of hemostasis -- stopping blood loss from damaged blood vessels. In hemostasis, a damaged blood vessel wall is plugged by a platelet and a fibrin-containing clot to stop the bleeding, so that the damage can be repaired (Citation 21). Coagulation involves a cellular (platelet) and protein (coagulation factor) component. When the lining of a blood vessel (endothelium) is damaged, platelets immediately form a plug at the site of the injury, while at the same time proteins in the blood plasma respond in a complex chemical reaction, rather like a waterfall, to form fibrin strands which reinforce the platelet plug (Citation 21). Bleeding disorders are due to to defects in the blood vessels, the coagulation mechanism, or the blood platelets. The blood coagulation mechanism is a process which transforms the blood from a liquid into a solid, and involves several different clotting factors. The mechanism generates fibrin when it is activated, which together with the platelet plug, stops the bleeding. When coagulation factors are missing or deficient, the blood does not clot properly and bleeding continues (Citation 21). |

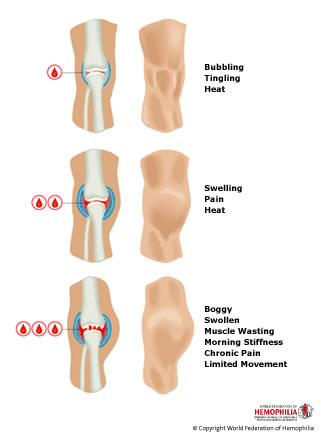

Types of Hemophilia Hemophilia A and Hemophilia B There are two main types of hemophilia: Hemophilia A (due to factor VIII deficiency) and Hemophilia B (due to factor IX deficiency). They are clinically almost identical and are associated with spontaneous bleeding into joints and muscles and internal or external bleeding after injury or surgery. After repeated bleeding episodes, permanent damage may be caused to the joints and muscles that have been affected, particularly the ankles, knees, and elbows (Citation 21). Although hemophilia A (also known as classic hemophilia) and hemophilia B (also known as Christmas disease) have similar signs and symptoms, they are caused by mutations in different genes. People with an unusual form of hemophilia B, known as hemophilia B Leyden, experience episodes of excessive bleeding in childhood but have few bleeding problems after puberty (Citation 22). Acquired Hemophilia Acquired hemophilia is very rare. The patient develops the condition during his/her lifetime and it does not have a genetic or heritable cause. It occurs when the body forms antibodies that attack one or more blood clotting factors, (usually factor VIII), thus preventing the blood clotting mechanism from working properly. Patients may be male or female and the pattern of bleeding is rather different from that of classical hemophilia, the joints being rarely affected. The disorder is particularly associated with old age and occasionally complicates pregnancy (Citation 21). |  |

| Who Does Hemophilia Affect? The 2 major forms of hemophilia occur much more commonly in males than in females. Approximately 1 in 5,000 males is born with Hemophilia A , and 1 in 30,000 males is born with Hemophilia B. Hemophilia affects people of all races and ethnic origins globally. The conditions are both X-linked and virtually all sufferers of hemophilia are males. Female carriers may also bleed abnormally, because some have low levels of the relative clotting factor (Citation 21). People with hemophilia have a genetic mutation in the affected gene on the X chromosome, which results in reduced production of Factor VIII or IX and creates a bleeding tendency, because coagulation takes much longer than normal, thus making the clot weak and unstable (Citation 21). Approximately 1/3 of patients with hemophilia have no family history of the disease, either because of new genetic mutations, or because previous affected generations either had daughters (who were carriers) or sons who died in early childhood from hemophilia or any other cause or who were not affected (Citation 21). |

Treatment and Drugs Hemophilia treatment varies depending on the severity of the condition: Mild hemophilia A. Treatment may involve slow injection of the hormone desmopressin (DDAVP) into a vein to stimulate a release of more clotting factor to stop bleeding. Occasionally, desmopressin is given as a nasal medication. Moderate to severe hemophilia A or hemophilia B. Bleeding may stop only after an infusion of clotting factor derived from donated human blood or from genetically engineered products called recombinant clotting factors. Repeated infusions may be needed if internal bleeding is serious. Hemophilia C. The clotting factor missing in this type of hemophilia (factor XI) is available only in Europe. In the U.S., plasma infusions are needed to stop bleeding episodes. |   |